Nearly half of L.A. tenants owe back rent

In a new survey of Los Angeles County renters, 49% of households reported that they were unable to pay all of their rent during the pandemic.

The study, by researchers from UCLA and the University of Southern California, found the median amount renters owe their landlords is $2,800. That suggests that countywide, tenants owe landlords upwards of $3 billion.

The findings are from one of a pair of surveys of 1,000 renters each—one conducted in July 2020, which focused on renters' ability to pay rent in the short term, and another in March 2021, asking about their ability to pay over the entirety of the pandemic.

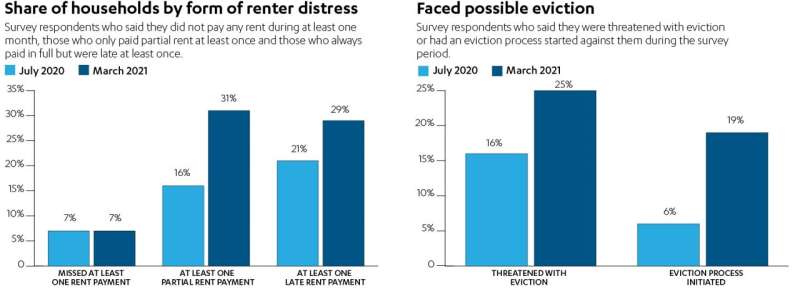

The preliminary results show that in both surveys, about 7% of renters missed a full rent payment in at least one of the three months before the study was conducted. But by the time the second survey was conducted, the share of renters paying less than the full amount to a landlord at least once during the crisis had almost doubled to 31%, up from 17% in July 2020.

The study was co-authored by Michael Manville, Paavo Monkkonen and Michael Lens, associate professors at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs; and Richard Green, director of the USC Lusk Center for Real Estate.

A slight majority of respondents reported paying their rent on time and in full, and many of those who owe rent said they were behind by less than a month. But other renters are emerging from the COVID-19 emergency in a financial hole they will struggle to climb out of on their own, the authors write in a research brief published today.

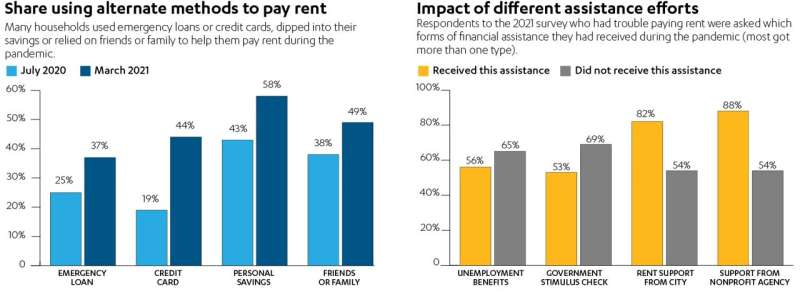

Of particular concern is evidence from the surveys that renters' debt rose sharply as the COVID-19 crisis dragged on. Only about 6% of Los Angeles tenants reported using a credit card to pay their rent prior to the pandemic. That figure rose to 19% of respondents in the early days of the emergency, and to 44% in the latest survey. Also in the 2021 survey, 49% said they turned to friends and family to help them pay rent, 58% dipped into their savings and another 37% reported taking out an emergency or payday loan.

The overall share of renters taking on debt reached 45% in the second survey, up from 32% in the first.

Other findings include:

- Just over 15% of tenants who were behind on their rent payments in 2020 had been threatened with eviction; that figure increased to 25% in the 2021 survey. Although an eviction moratorium is still in effect in Los Angeles County, tenants can still be threatened with evictions or have evictions initiated against them; a court won't act until the moratorium ends.

- Similarly, 6% reported in 2020 that an eviction had been initiated against them. In 2021, that percentage tripled to 18%.

- In the 2021 survey, about 68% of all respondents said they had received federal aid during the pandemic, and about 15% reported getting local aid.

California's eviction moratorium will remain in place through at least September, and the brief notes that the state has committed to helping renters pay the back rent they owe. Through existing rental assistance programs, which generally require that both landlords and tenants agree to participate, the state or city pays landlords on the behalf of tenants who qualify for assistance.

The problem? The data show that many tenants owe money to people or institutions other than their landlords, and the researchers write that many may be in that position precisely because they were deeply concerned about their housing security.

The report suggests a solution often advocated by economists as the best way to help people facing financial trouble: Just give people money. Distributing cash to tenants who are financially distressed would allow them to pay back whomever is owed the money—a landlord, another creditor or a family member.

"Programs where the government pays a landlord are sometimes justified as ways to prevent fraud or misuse," Manville said. "And we should certainly be concerned about fraud. But we need to weigh those concerns against the possibility that an overly cautious program will deny needed assistance to some people who are in real financial trouble."

To allay concerns about fraudulent claims—which in most government redistribution programs are very rare—the authors suggest ways the state could ask for evidence of debt, lost work or income.

The 2021 survey was funded and produced by the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies in partnership with the USC Lusk Center for Real Estate, the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs and the Committee for Greater LA.

Provided by University of California, Los Angeles