Credit: AI-generated image (disclaimer)

Earth is the only planet we know of with continents, the giant landmasses that provide homes to humankind and most of Earth's biomass.

However, we still don't have firm answers to some basic questions about continents: how did they come to be, and why did they form where they did?

One theory is that they were formed by giant meteorites crashing into Earth's crust long ago. This idea has been proposed several times, but until now there has been little evidence to support it.

In new research published in Nature, we studied ancient minerals from Western Australia and found tantalizing clues suggesting the giant impact hypothesis might be right.

How do you make a continent?

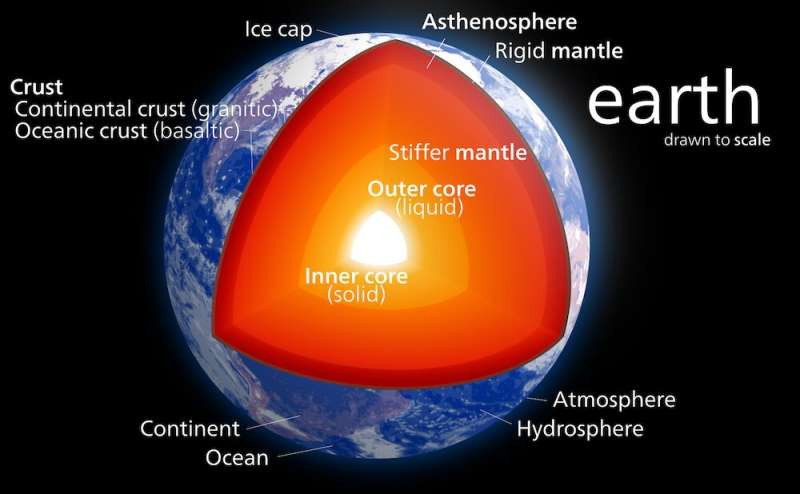

The continents form part of the lithosphere, the rigid rocky outer shell of Earth made up of ocean floors and the continents, of which the uppermost layer is the crust.

The crust beneath the oceans is thin and made of dark, dense basaltic rock which contains only a little silica. By contrast, the continental crust is thick and mostly consists of granite, a less dense, pale-colored, silica-rich rock that makes the continents "float."

Beneath the lithosphere sits a thick, slowly flowing mass of almost-molten rock, which sits near the top of the mantle, the layer of Earth between the crust and the core.

If part of the lithosphere is removed, the mantle beneath it will melt as the pressure from above is released. And impacts from giant meteorites—rocks from space tens or hundreds of kilometers across—are an extremely efficient way of doing exactly that!

The internal structure of Earth. Credit: Kelvin Song / Wikimedia, CC BY

What are the consequences of a giant impact?

Giant impacts blast out huge volumes of material almost instantaneously. Rocks near the surface will melt for hundreds of kilometers or more around the impact site. The impact also releases pressure on the mantle below, causing it to melt and produce a "blob-like" mass of thick basaltic crust.

This mass is called an oceanic plateau, similar to that beneath present-day Hawaii or Iceland. The process is a bit like what happens if you are hit hard on the head by a golf ball or pebble—the resulting bump or "egg" is like the oceanic plateau.

Our research shows these oceanic plateaus could have evolved to form the continents through a process known as crustal differentiation. The thick oceanic plateau formed from the impact can get hot enough at its base that it also melts, producing the kind of granitic rock that forms buoyant continental crust.

Are there other ways to make oceanic plateaus?

There are other ways oceanic plateaus can form. The thick crusts beneath Hawaii and Iceland formed not through giant impacts but "mantle plumes," streams of hot material rising up from the edge of Earth's metallic core, a bit like in a lava lamp. As this ascending plume reaches the lithosphere it triggers massive mantle melting to form an oceanic plateau.

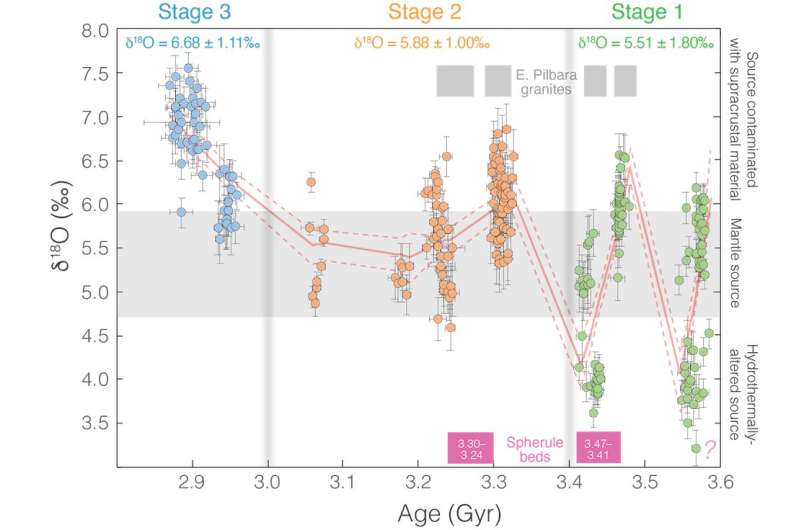

So could plumes have created the continents? Based on our studies, and the balance of different oxygen isotopes in tiny grains of the mineral zircon, which is commonly found in tiny quantities in rocks from the continental crust, we don't think so.

Zircon δ18O (‰) vs age (Ma) for individual dated magmatic zircon grains from the Pilbara Craton. The horizontal grey band shows the array of δ18O in mantle zircon (5.3 +/– 0.6‰, 2 s.d.). The vertical grey bands subdivide the data into three stages, as discussed in the paper. The pink boxes represent the age of deposition of high-energy impact deposits (spherule beds) from the Pilbara Craton and more widely.

Zircon is the oldest known crustal material, and it can survive intact for billions of years. We can also determine quite precisely when it was formed, based on the decay of the radioactive uranium it contains.

What's more, we can find out about the environment in which zircon formed by measuring the relative proportion of isotopes of oxygen it contains.

We looked at zircon grains from one of the oldest surviving pieces of continental crust in the world, the Pilbara Craton in Western Australia, which started forming more than 3 billion years ago. Many of the oldest grains of zircon contained more light oxygen isotopes, which indicate shallow melting, but younger grains contain a more mantle-like balance isotopes, indicating much deeper melting.

This "top-down" pattern of oxygen isotopes is what you might expect following a giant meteorite impact. In mantle plumes, by contrast, melting is a "bottom-up" process.

Journal information: Nature

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()