This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

Coming in hot: NASA's Chandra checks habitability of exoplanets

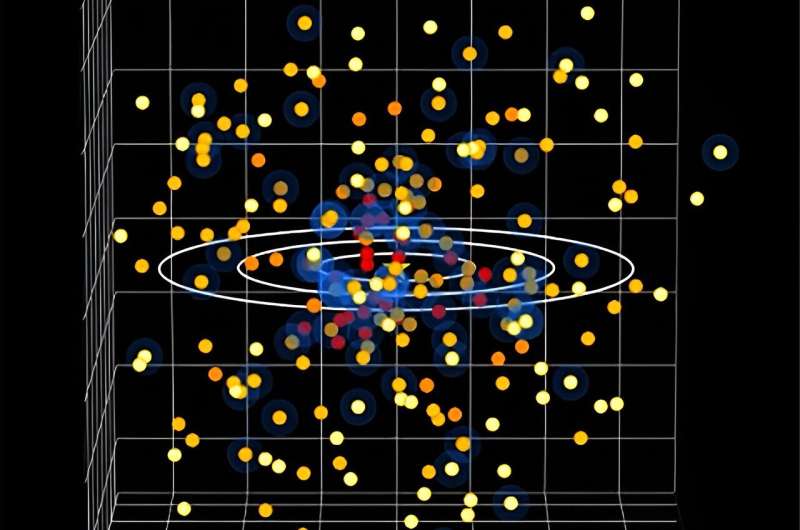

Using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and ESA's (European Space Agency's) XMM-Newton, astronomers are exploring whether nearby stars could host habitable exoplanets, based on whether they emit radiation that could destroy potential conditions for life as we know it. This type of research will help guide observations with the next generation of telescopes aiming to take the first images of planets like Earth.

A team of researchers has examined stars that are close enough to Earth that future telescopes could take images of planets in their so-called habitable zones, defined as orbits where the planets could have liquid water on their surfaces. Their results were presented at the 244th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Madison, Wisconsin.

Any images of planets will be single points of light and will not directly show surface features like clouds, continents, and oceans. However, their spectra—the amount of light at different wavelengths—will reveal information about the planets' surface compositions and atmospheres.

There are several factors influencing what could make a planet suitable for life as we know it. One of those factors is the amount of harmful X-rays and ultraviolet light it receives from its host star, which can damage or even strip away the planet's atmosphere.

"Without characterizing X-rays from its host star, we would be missing a key element on whether a planet is truly habitable or not," said Breanna Binder of California State Polytechnic University in Pomona, who led the study. "We need to look at what kind of X-ray doses these planets are receiving."

Binder and her colleagues began with a list of stars that are close enough to Earth for which future ground and space-based telescopes could obtain images of planets within their habitable zones. These future telescopes include the Habitable Worlds Observatory and ground-based extremely large telescopes.

Based on X-ray observations of some of these stars using data from Chandra and XMM-Newton, Binder's team examined which stars could host planets with hospitable conditions for life to form and prosper.

The team studied how bright the stars are in X-rays, how energetic the X-rays are, and how much and how quickly they change in X-ray output, for example, due to flares. Brighter and more energetic X-rays can cause more damage to the atmospheres of orbiting planets.

"We have identified stars where the habitable zone's X-ray radiation environment is similar to or even milder than the one in which Earth evolved," said Sarah Peacock, a co-author of the study from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. "Such conditions may play a key role in sustaining a rich atmosphere like the one found on Earth."

The researchers used data available in archives from almost 10 days of Chandra observations and about 26 days of XMM observations to examine the X-ray behavior of 57 nearby stars, some of them with known planets. Most of these are giant planets like Jupiter, Saturn or Neptune, while only a handful of planets or planet candidates could be less than about twice as massive as Earth.

There are likely many more planets orbiting stars in the sample, especially ones similar in size to Earth, that so far remain undetected. Transit studies, which look for tiny dips in light when planets pass in front of their stars from our perspective, miss many planets because special geometry is required to spot them. This means the chances of detecting transiting planets in a small sample of stars is low; only one exoplanet in the sample was picked up by transits.

The other main technique for detecting planets is via detection of the wobbling of a star induced by the orbiting planets, and this technique is mainly sensitive to finding giant planets relatively close to their host stars.

"We don't know how many planets similar to Earth will be discovered in images with the next generation of telescopes, but we do know that observing time on them will be precious and extremely difficult to obtain," said co-author Edward Schwieterman of the University of California at Riverside. "These X-ray data are helping to refine and prioritize the list of targets and may allow the first image of a planet similar to Earth to be obtained more quickly."

Provided by Chandra X-ray Center