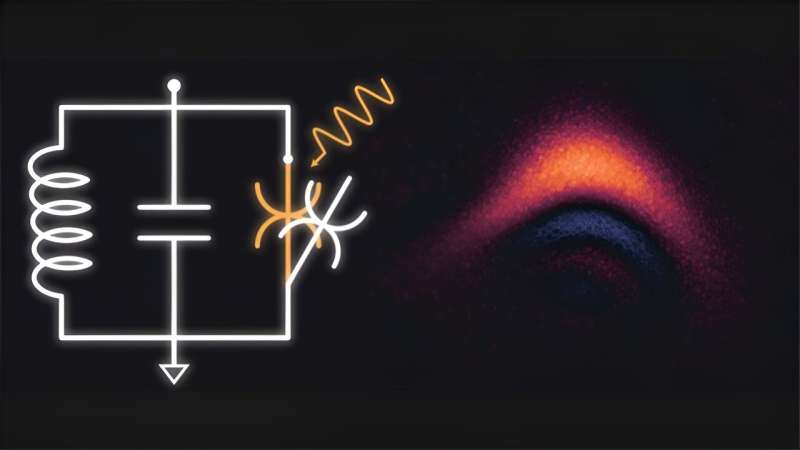

The circuit diagram to the left illustrates how the Chalmers researcher team was able to turn on and off different operations by sending microwave pulses (wiggly arrow) to the control system embedded in the oscillator. The researchers used the system to generate a so-called cubic phase state which is a quantum resource for quantum error correction. The blue areas to the right are so called Wigner negative regions—a clear signature of the quantum properties of the state. Credit: Chalmers University of Technology/Timo Hillman

The potential of quantum computers is currently thwarted by a trade-off problem. Quantum systems that can carry out complex operations are less tolerant to errors and noise, while systems that are more protected against noise are harder and slower to compute with.

Now a research team from Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden has created a unique system that combats the dilemma, thus paving the way for longer computation time and more robust quantum computers.

For the impact of quantum computers to be realized in society, quantum researchers first need to deal with some major obstacles. So far, errors and noise stemming from, for example, electromagnetic interference or magnetic fluctuations, cause the sensitive qubits to lose their quantum states—and subsequently their ability to continue the calculation. The amount of time that a quantum computer can work on a problem is thus so far limited.

Additionally, for a quantum computer to be able to tackle complex problems, quantum researchers need to find a way to control the quantum states. Like a car without a steering wheel, quantum states may be considered somewhat useless if there is no efficient control system to manipulate them.

However, the research field is facing a trade-off problem. Quantum systems that allow for efficient error correction and longer computation times are on the other hand deficient in their ability to control quantum states—and vice versa. But now, a research team at Chalmers University of Technology has managed to find a way to battle this dilemma.

"We have created a system that enables extremely complex operations on a multi-state quantum system, at an unprecedented speed." says Simone Gasparinetti, leader of the 202Q-lab at Chalmers University of Technology and senior author of the study.

Deviates from the two-quantum-state principle

While the building blocks of a classical computer, bits, have either the value 1 or 0, the most common building blocks of quantum computers, qubits, can have the value 1 and 0 at the same time—in any combination. The phenomenon is called superposition and is one of the key ingredients that enable a quantum computer to perform simultaneous calculations, with enormous computing potential as a result.

However, qubits encoded in physical systems are extremely sensitive to errors, which has led researchers in the field to search for ways to detect and correct these errors. The system created by the Chalmers researchers is based on so-called continuous-variable quantum computing and uses harmonic oscillators, a type of microscopic component, to encode information linearly.

The oscillators used in the study consist of thin strips of superconducting material patterned on an insulating substrate to form microwave resonators, a technology fully compatible with the most advanced superconducting quantum computers.

The method is previously known in the field and departs from the two-quantum state principle as it offers a much larger number of physical quantum states, thus making quantum computers significantly better equipped against errors and noise.

"Think of a qubit as a blue lamp that, quantum mechanically, can be both switched on and off simultaneously. In contrast, a continuous variable quantum system is like an infinite rainbow, offering a seamless gradient of colors. This illustrates its ability to access a vast number of states, providing far richer possibilities than the qubit's two states," says Axel Eriksson, researcher in quantum technology at Chalmers University of Technology and lead author of the study.

More information: Axel M. Eriksson et al, Universal control of a bosonic mode via drive-activated native cubic interactions, Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-46507-1

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by Chalmers University of Technology