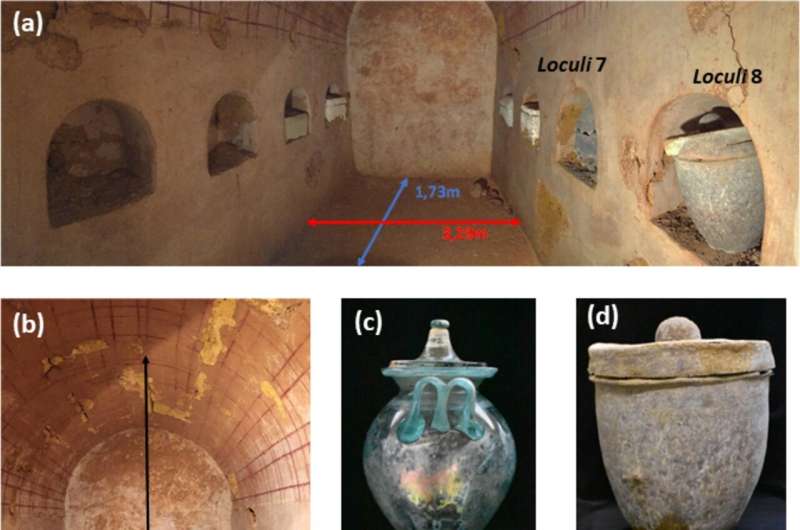

The wine in the glass urn. Credit: Juan Manuel Román

A white wine over 2,000 years old, of Andalusian origin, is the oldest wine ever discovered.

Hispana, Senicio and the other four inhabitants (two men and two women, their names unknown) of a Roman tomb in Carmona, discovered in 2019, probably never imagined that what for them was a funerary ritual would end up being momentous 2,000 years later, for an entirely different reason.

As part of that ritual, the skeletal remains of one of the men were immersed in a liquid inside a glass funerary urn. This liquid, which over time has acquired a reddish hue, has been preserved since the first century AD, and a team with the Department of Organic Chemistry at the University of Cordoba, led by Professor José Rafael Ruiz Arrebola, in collaboration with the City of Carmona, has identified it as the oldest wine ever discovered, thus toppingthe Speyer wine bottle discovered in 1867 and dated to the fourth century AD, preserved in the Historical Museum of Pfalz (Germany).

"At first we were very surprised that liquid was preserved in one of the funerary urns," explains the City of Carmona's municipal archaeologist Juan Manuel Román. After all, 2,000 years had passed, but the tomb's conservation conditions were extraordinary; fully intact and well-sealed ever since, the tomb allowed the wine to maintain its natural state, ruling out other causes such as floods, leaks inside the chamber, or condensation processes.

The challenge was to dispel the research team's suspicions and confirm that the reddish liquid really was wine rather than a liquid that was once wine but had lost many of its essential characteristics. To do this, they ran a series of chemical analyses at the UCO's Central Research Support Service (SCAI) and published them in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

They studied its pH, absence of organic matter, mineral salts, the presence of certain chemical compounds that could be related to the glass of the urn, or the bones of the deceased; and compared it to current Montilla-Moriles, Jerez and Sanlúcar wines. Thanks to all this, they had their first evidence that the liquid was, in fact, wine.

But the key to its identification hinged on polyphenols, biomarkers present in all wines. Thanks to a technique capable of identifying these compounds in very low quantities, the team found seven specific polyphenols also present in wines from Montilla-Moriles, Jerez and Sanlúcar.

(a), (b) Funeral chamber. (c) Urn in niche 8. (d) Lead case containing the urn. (e) Reddish liquid contained in the urn. Credit: Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2024.104636

The absence of a specific polyphenol, syringic acid, served to identify the wine as white. Despite this, and the fact that this type of wine accords with bibliographic, archaeological and iconographic sources, the team clarifies that the fact that this acid is not present may be due to degradation over time.

Most difficult to determine was the origin of the wine, as there are no samples from the same period with which to compare it. Even so, the mineral salts present in the tomb's liquid are consistent with the white wines currently produced in the territory, which belonged to the former province of Betis, especially Montilla-Moriles wines.

More information: Daniel Cosano et al, New archaeochemical insights into Roman wine from Baetica, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2024.104636

Journal information: Journal of Archaeological Science

Provided by University of Córdoba