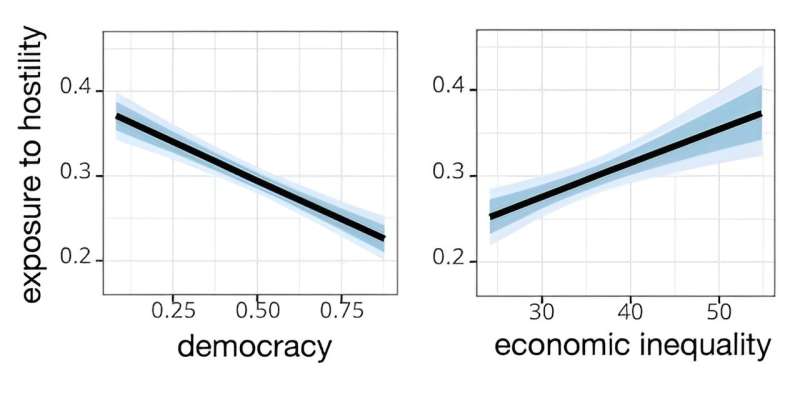

These graphs show the statistical association between exposure to online political hostility and the liberal democracy index (V-dem) or the level of economic inequality (World Bank Gini estimates) in 30 countries. Credit: Bor, Marie, Pradella, Petersen, Fourni par l'auteur

Once upon a time, newly minted graduates dreamt of creating online social media that would bring people closer together.

That dream is now all but a distant memory. In 2024, there aren't many ills social networks don't stand accused of: the platforms are singled out for spreading "fake news," for serving as Russian and Chinese vehicles to destabilize democracies, as well as for capturing our attention and selling it to shadowy merchants through micro targeting. The popular success of documentaries and essays on the allegedly huge social costs of social media illustrates this.

One of those critical narratives, in particular, accuses digital platforms and their algorithms of amplifying political polarization and hostility online. Some have gone so far as to say that in online discussions, "anyone can become a troll," i.e., turn into an offensive and cynical debater.

Recent scholarship in quantitative social sciences and scientific psychology, however, provides important nuance to this pessimistic discourse.

The importance of social context and psychology

To start with, several studies suggest that if individuals regularly clash over political issues online, this is partly due to psychological and socioeconomic factors independent of digital platforms.

In our large scale cross-cultural study, we surveyed more than 15,000 people about their experiences of online conversations about social issues. Interviews were carried out via representative panels in 30 countries across six continents. Our first finding is that it is in economically unequal and less democratic countries (e.g., Turkey, Brazil) that individuals are most often victims of online hostility on social media (e.g., insults, threats, harassment, etc.). A phenomenon which seems to derive from frustrations generated by more repressive social environments and political regimes.

Our study also shows that the individuals who indulge most in online hostility are also those who are higher in status-driven risk taking. This personality trait corresponds to an orientation towards dominance, i.e., a propensity to seek to submit others to one's will, for instance through intimidation. According to our cross-cultural data, individuals with this type of dominant personality are more numerous in unequal and non-democratic countries. Similarly, independent analyses show that dominance is a key element in the psychology of political conflict, as it also predicts more sharing of "fake news" mocking or insulting political opponents, and more attraction to offline political conflict, in particular.

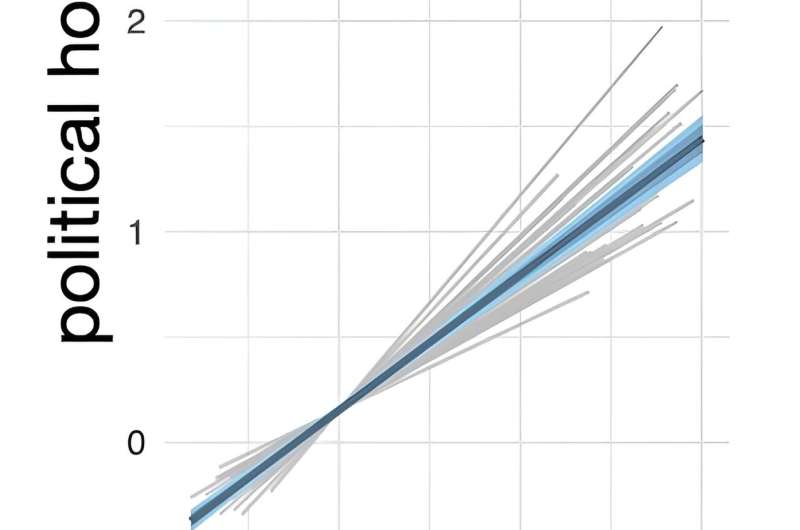

Replicating a previous study, we also find that individuals high in status-driven risk taking, who most admit to behaving in a hostile manner online, are also those most likely to interact in an aggressive or toxic manner in face-to-face discussions (the correlation between online and hostility is quite strong: β = 0.77).

The level of online political hostility as a function of the level of status-driven risk taking (15 000 users surveyed). The light grey lines are estimates by country, the dark line represents the overall average association. Credit: Bor, Marie, Pradella, Petersen, Fourni par l'auteur

In summary, online political hostility appears to be largely the product of the interplay between particular personalities and social contexts repressing individual aspirations. It is the frustrations associated with social inequality that have made these people more aggressive, activating tendencies to see the world in terms of "us" vs. "them". On a policy level, if we are to bring about a more harmonious Internet (and civil society), we will likely have to tackle wealth inequality and make our political institutions more democratic.

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()